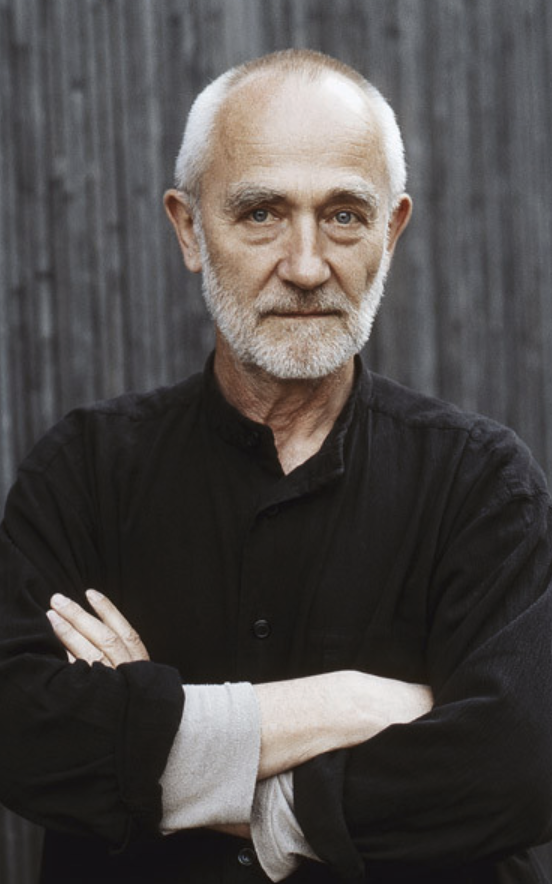

The Legendary Peter Zumthor

Introduction

Perhaps my favourite material master and architect, Peter Zumthor is a master Swiss architect whose work has become a symbol of material mastery and sensory rich architecture. Zumthor, who was awarded the prestigious Pritzker Prize in 2009, is often described as the anti-starchitect. Rather than working on big projects or having an internationally renowned large firm, Zumthor decides to work in his own home, and is more concerned about the tactility and ‘physical emotion’ of space. In this blog post, we’ll delve into his practice, his historical background, the core of his philosophical approach, the methods and tools he uses, how his practice is unique, and his continuing relevance.

Early Life & Practice Background

Born on April 26, 1943, Zumthor grew up in a very creative household. HIs father was a furniture maker and joiner, and Zumthor followed in his creative footsteps. Zumthor studied at the Kunstgewerbeschule in Basel (now University of Art and Design) and later at the Pratt Institute in New York. After completing his studies, he set up his own studio in 1979 in Haldenstein, Switzerland. He chose to keep this studio small, making it part of his house, and making it incredibly hard to get a job. The reason for this matched his philosophy of practice, remaining hands-on and deeply involved with every project he chooses to take on.

His early works include thoughtful, modest commissions — chapels, small museums, restorations — where craft, material and site context were central. Over time his reputation grew, but his methods remained deliberate and slow rather than spectacular.

Philosophy: What Architecture Means to Zumthor

Sensory Experience & Atmosphere

At the heart of Zumthor’s approach lies the belief that architecture is first and foremost experience. In an interview he said:

“We actually never talk about form in the office. We talk about construction, we can talk about science, and we talk about feelings … From the beginning the materials are there, right next to the desk.”

He argues that architecture is “not about façade, elevation, making image, making money. My passion is creating space.”

His designs aim to create what he calls “presence” — a moment where past and future fall away and one is simply in a space. For him:

“Presence is like a gap in the flow of history, where all of [a] sudden it is not past and not future.”

In short, Zumthor believes that architecture should be aimed at evoking emotion through space, and not through flashy or imposing structures. He does this by centering his craft around Materiality and construction.

Materiality & Construction

Zumthor repeatedly emphasizes that architecture begins with the material:

“When I start, my first idea for a building is with the material. I believe architecture is about that. It’s not about paper, it’s not about forms. It’s about space and material.”

He places enormous importance on tectonics — how materials join, age, weather, and resonate. One writer captured it as:

“The real core of all architectural work lies in the act of construction.”

His craftsman’s background shows in the fact that for Zumthor details matter deeply — he might obsess over how a handle feels, how stone is laid, how light falls. In one interview he reflected how, decades later, he still noticed small imperfections in his older buildings.

Context, Memory & Time

Unlike most contemporary architecture that seems imposing or commercialized, Zumthor’s work is grounded in context, memory and time. He studies the sites surrounding the environment, its culture, way of life, and climate in order to best plan his design, making his work differ from each site, and never having a ‘distinctive feature’. In Zumthor’s view, architecture should ‘oppose resistance’, and bring out the subtleties of place.

“Emotion reveals the ‘authentic core’ of things.”

Thus, his architecture is less about style and more about being, about how people inhabit and remember spaces.

Practice & Methods: How Zumthor Works

Small Studio Scale & Deep Involvement: Zumthor chooses to keep his studio/atelier size small, so he can be involved with every aspect of the design process, including construction.

Material Prototyping & Model Making: Zumthor begins all his designs with material sampling, especially materials near the site. He then creates tiny models on his desk, even quoting that “materials are there, right next to the desk.”

Iterative, Slow Development: For Zumthor, time is not of concern. His projects take years to develop, each with careful thought and reflection. For example in his most famous work Therme Vals, he spent years researching about properties of stone, water and atmosphere.

Site-and-Material-Driven: Zumthor often questions the site, including its location, environment and cultural traditions, believing these factors should be grounded in ‘physical design’, rather than remaining something abstract or intangible.

Aiming for Atmosphere not Image: The goal is not to create a photo-friendly façade but a lived space. He observed: “If a space doesn’t get to you, then I am not interested.”

Selected Key Projects

Therme Vals, Switzerland (1996) – A spa built of local quartzite slabs, exploring water, stone, light, and the alpine landscape to create a rich sensory experience. (illustrarch)

Bruder Klaus Field Chapel, Germany (2007) – A rustic concrete chamber built with logs burned out to leave charred interior surfaces, evoking ritual, materiality and silence. (The New Yorker)

Kolumba Museum, Cologne, Germany (2007) – Built upon ruins of a Gothic church, the museum merges old and new, brick and glass, silence and art. (LA)

Steilneset Memorial to the Victims of Witch Trials, Vardø, Norway (2011) – A contemplative memorial with a long corridor of fibreglass and small windows, highly atmospheric and minimal. (LA)

Impact & Legacy

Zumthor’s influence in architecture can be represented through quality over quantity. HIs exceptional intellectual depth in research serves as a counter to technology driven and parametric design trends that have influenced modern architecture. Zumthor refocuses architecture on the impact of materials, atmosphere and tactility in modern age, grounding design in tradition, and truly makes architecture become timeless, challenging architects to understand how space changes and feels over time, and its relation to human conditions.