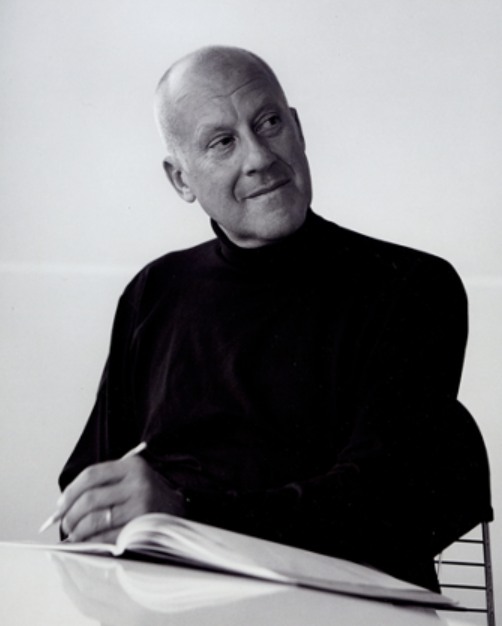

Norman Foster

Introduction

If we talk about the architect, then it would probably be Norman Foster. He is probably the most influential architect of the century, and a pioneer of technological innovation in architecture. His works include the most iconic buildings, airports and structures across the globe, and has his own distinctive design taste and philosophy. More than just a stylistic icon, Foster’s practice explores the intersection of technology, environment, and urban life. In this article we’ll look at his background and practice, his design philosophy, signature methods and tools, what makes his approach unique, and his legacy today.

Early Life & Career

Born on June 1st 1935 in Reddish Stockport (near Manchester), Foster grew up in a modest middle class family, his father being a machine painter and his mother working in a bakery. Foster then studied architecture and city planning at the University of Manchester, and later on a Henry Fellowship to Yale School of architecture. After graduating, he joined a practice working with 3 other partners before venturing off and creating his firm today – the famous Foster + Partners. His early works include the Sainsbury Centre for Visual Arts in Norwich (1978) which had a ‘shed’ like logic , having a clear structure and flexible interior space, and an emphasis on transparency and infrastructure. Later on, he set his mark on designing the Millau Viaduct, HSBC headquarters in Hong Kong, numerous airports and Apple Park.

Design Philosophy & Intellectual Framework

Foster’s architectural philosophy can be distilled into several key themes

1. Technology and Infrastructure first.

Foster treats structure and services as a basis for his architecture. Compared to other bold architects who seek to work innovative structures into their design (i.e Zaha Hadid), Foster sees structure as the basis for his design, an integral part to his expression. If we look at his works, we can see he often exposes the ducts, trusses and key structural elements, as seen below in the HSBC Headquarters in Hong Kong, where circulation, trusses and each layer create a transparent atrium. Additionally, within his own firm, he set up branches for technology and research, engineering and climate and sustainable design, showing his deep fascination with technology and infrastructure towards architecture as a discipline, and having an interdisciplinary approach to practice.

2. Environment, Sustainability & Efficiency

Foster has long been advocating for sustainable architecture that responds to climate change:

“Architecture is generated by people’s needs, both spiritual and material, and that has always been a guiding principle.”

He also states:

“Environmental issues affect architecture at every level … from site, orientation, form, structure, materials, heating and ventilation systems.”

3. Urbanism and Infrastructure Scale

Foster believes in architecture for people, thus most of his projects work on larger scales – airports, stadiums, bridges and even city districts. Some call him the commercial architect with the amount of high profile contracts he gets.

4. Form Follows Function… But Complexly

To some who try to understand form follows function, they may not understand it inherently, and most designs look unclear. Foster does the same, he complicates the line to a point to almost blurring it. He uses the usual diagrams, engineering logic, and environment to shape his form rather than the function, yet experiencing it feels efficient as well, forming a complex dichotomy in terms of “how did he do it?”

5. Reinvention, Regeneration & Legacy Work

Foster engages with major historical buildings and complex urban sites. His renovation of the Reichstag in Berlin (adding the glass dome) and the Great Court of the British Museum in London are as much acts of civic regeneration as architecture.

Signature Methods, Tools & Process

Although some of these methods overlap with other practices, they are oftentimes the most used part of their design process.

Diagrammatic analysis: Foster + Partners uses and creates new digital modelling tools and technology to analyze structure, daylight and airflow. Even in the early stages of his career, Foster collaborated with Buckminster Fuller on gridshells and lightweight structures, using technology and analysis to find bold innovative design solutions.

Prefabrication and modular construction: Many of his buildings use modular units, steel and glass systems, often constructed off-site and assembled on-site to maintain quality, speed and precision.

Exposed structural systems: Beams, bracing, trusses, service cores are treated as architectural elements and are oftentimes more exposed than hidden, sometimes creating the feeling that the building continues to evolve rather than stay static.

Sustainability integrated into form: Natural ventilation, sun-shading, building skins, daylighting, atria open to sky, even setting up the own sustainability and climate department shows their key ethical environmental considerations when laying out their design approaches.

Large-scale coordination: For airports, masterplans, infrastructure works, the process includes long lead times, many consultants, logistics, and internal research. Foster + Partners has offices across multiple countries to manage scale, and is one of, if not the largest architecture firm internationally.

Research-Driven and Forward-Thinking: Through the Norman Foster Foundation he supports research on the future of cities, materiality and architecture. He also sponsors scholarships and gives critiques at architecture school, as foster believes in the power and continuation of education.

Selected Major Projects and key features

HSBC Headquarters, Hong Kong (1986): A pioneering high-tech building with modular design and external services. Fun fact, it was designed so that every part of the building could be stripped and packed away to Singapore, in the event of a poor handover of HK.

Reichstag Dome, Berlin (1999): Renovation adding a glass dome symbolising transparency in government, integrating old and new.

30 St Mary Axe (“The Gherkin”), London (2004): Iconic tower with aerodynamic form and sustainable skin.

Beijing Capital International Airport, Terminal 3 (2008): Massive infrastructure project integrating transport, architecture, landscape.

Apple Park, Cupertino (2018): A large-scale campus for Apple, emphasizing sustainability, occupant wellbeing and technological integration.

Norman Foster’s influence on architecture and urbanism is unrivaled in modern day, pushing the boundaries of architecture, technology and urban planning. Although some may criticize him for only doing large scale commercial projects, Foster’s approach to design and his belief in technology and sustainability has spread throughout architecture and urban planning, being one of the key figures in defining modern architecture. At age 90, he continues to engage with major civic and urban projects, mentoring younger architects and leading the Norman Foster Foundation’s research on cities of the future. His practice reminds us that architecture, despite grounded in history and tradition, will constantly change and be shaped by technology.