Tatiana Bilbao: Architecture as Care — an in-depth look at her practice and philosophy

Known for her creative collages that are seen throughout architecture school, Tatiana Bilbao is one of the world's leading architects, and her works focuses on social housing, civic infrastructure and environmental interventions, being both pragmatically and politically engaged with architecture. In recent years, she began to practice architecture as a form of care, turning a key interest in affordability and adaptability of architecture. This post unpacks her biography, key projects, recurring methods and the ethical core that makes her work distinctive.

A Quick Biography

Born in 1972 in Mexico city, Bilbao grew up in a family of architects. She studied at Universidad Iberoamericana and has taught at the most famous architecture schools around the world. She now has her own studio Tatiana Bilbao Estudio, teaches in the U.S, and seeks to connect design to social solutions treating architecture as a civic tool: inexpensive housing prototypes, landscape and park masterplans, community-driven public spaces and research projects — all aimed at redistributing design’s benefits for everyone.

Core idea: design as care

Bilbao frames architecture as care. She says “by putting humans in the center,” insisting that spaces must protect and inspire humanity. Like Shigeru Ban, Bilbao refuses to treat sustainability as an ‘optional add-on’ but a fundamental must have in architectural design. However, Bilbao rejects the norms of sustainability and uses interventions that are inspired by the site’s cultural and environmental context, even creating jobs and increasing resilience.

This ethical commitment drives everything from how she approaches housing prototypes to how she runs public engagement exercises.

Three projects that show her method

1) Housing prototypes (Housing+ / Acuña prototype) — adaptability as dignity

Bilbao’s housing research and prototypes are perhaps the best examples of her design philosophy. This can be best shown through her low-cost, highly adaptable housing modules to give every family access to affordable housing. Her models redesigned the traditional pitched roof dwelling by constructing it using modular parts, and flexible interior wall partitions that can be modified to suit people's needs. It’s not as ‘aesthetically’ imposing or appealing, but grounded in her ethical design approach of social intervention, a way to improve housing most efficiently for people. This work has been widely published and exhibited as an alternative to one-size-fits-all developer housing.

2) Culiacán Botanical Garden & Pavilion — pattern, landscape and local identity

Another part of her work is her respect for process. Rather than focusing on the outcome of her building design, she develops meticulous masterplans and traces patterns from existing trees and local circulations, then she places her design within that context, making it easy for locals to use and made with sustainable materials. It’s a good example of her incremental, site-sensitive method.

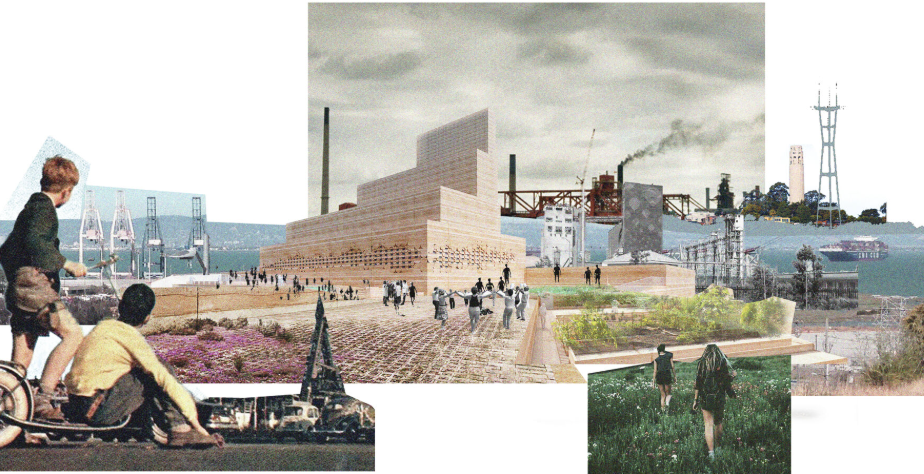

3) Hunters Point Substation / public design work — co-design and programmatic mapping

In projects like Hunter Point in New York, and public plaza spaces like Exhibit Columbus, Bilbao uses maps, models and simple geometries that create an inviting space with civic functions. Rather than creating a grounded structure, she uses blocks so that the public and redesign and reconfigure it, reframing the role of an architect as an initiator rather than a designer.

Recurrent tactics and tools

Collage and hand drawing as thinking tools.

Famous for her collages, she uses these as her main medium ( along with hand sketches) to see human scale and breathe life into models. She uses these analog practices to keep the imagination grounded in everyday experience rather than visual spectacle.

Community-facing models for participation. As seen before, Bilbao is known for creating simple models that invite public participation, a recurring theme in both lectures and design. Doing so, she grounds design within human thought and free will.

Material pragmatism. Bilbao chooses materials for cultural fit, climate performance and workability (often local masonry, concrete, wood), not for fashion. She seeks craft-friendly methods that stimulate local employment.

Teaching, exhibitions and narrative work

Bilbao extends influence by teaching (Yale, Columbia, Cornell among others), curating exhibitions and publishing work that reframes architecture as collective practice. She places teams in long-term community relationships rather than episodic consultant roles. Exhibitions like “The House and the City” and public installations showcase how simple spatial rules (shared kitchens, adaptable rooms, collective courtyards) can remake social life — shifting the discourse from spectacle toward systems.

A few signature quotes that reveal her mind

“Architecture is a primary form of care. I design by putting humans in the center and caring about them.” — Tatiana Bilbao.

“I hate the word ‘sustainability’ because I think it has become a word that can qualify a type of architecture, and for me it should be embedded.” — Bilbao (interview). This line captures her impatience with buzzwords and her insistence on embedded practice.

Bilbao’s ethic of care and modesty has also produced debates. Critics ask whether modest prototypes scale politically in contexts of entrenched inequality and powerful developers; whether incrementalism delays systemic reforms (land policy, finance). Others applaud her refusal to aestheticize poverty — but worry the same approach can be co-opted as low-cost “greenwashing” by institutions. Bilbao counters by insisting that design must be coupled with policy and community agency, not merely technocratic fixes.

Why her practice is influential now

Three reasons make Bilbao particularly relevant in 2025:

Climate and housing crises demand low-tech, socially aware solutions. Her prototypes and participatory methods are replicable and resilient.

A shift toward civic practice. More architects are being asked to work on public infrastructure and participatory processes; Bilbao’s studio models how to do this with design rigor.

Discursive leadership. Through exhibitions, teaching and public platforms she shapes how policymakers and clients think about housing, community and sustainability.

Tatiana Bilbao is not interested in architecture as a signature object. Her practice repeatedly asks: Who benefits from architecture? — and then designs systems so the answer is broad, inclusive and adaptive. Whether through an $8,000 prototype house, a botanical masterplan, or a community workshop, Bilbao’s architecture operates as infrastructure for care: modest, evidence-driven and human-scale. In a profession often seduced by spectacle, her insistence on craft, participation and ethics feels less contrarian than necessary.