Renzo Piano: The Lightness of Making — an in-depth look at his practice and philosophy

Renzo Piano’s architecture is bold, it seems almost like an engineer and artist merging their brains into one. He is one of the few late-20th/ early 21st century architects whose work is distinctive enough from a distance away, work bathed in natural light, fine technical systems, elegant design and structural clarity. In this post, we look at Piano’s life, and delve into the nuances of his practice, his belief and workflow, but most importantly we examine how his buildings embody a particular ethical project — architecture made to last by being honest, light, and useful.

A short biography and the formation of a practice

Born in 1937, Renzo Piano studied at the famous Politecnico di Milano before traning as an apperntiance under Louis Kahn in Philadelphia. Working under Kahn, Piano was exposed to his influence of design, one that eventually shaped his own philosophy – balancing structure with sensibility.

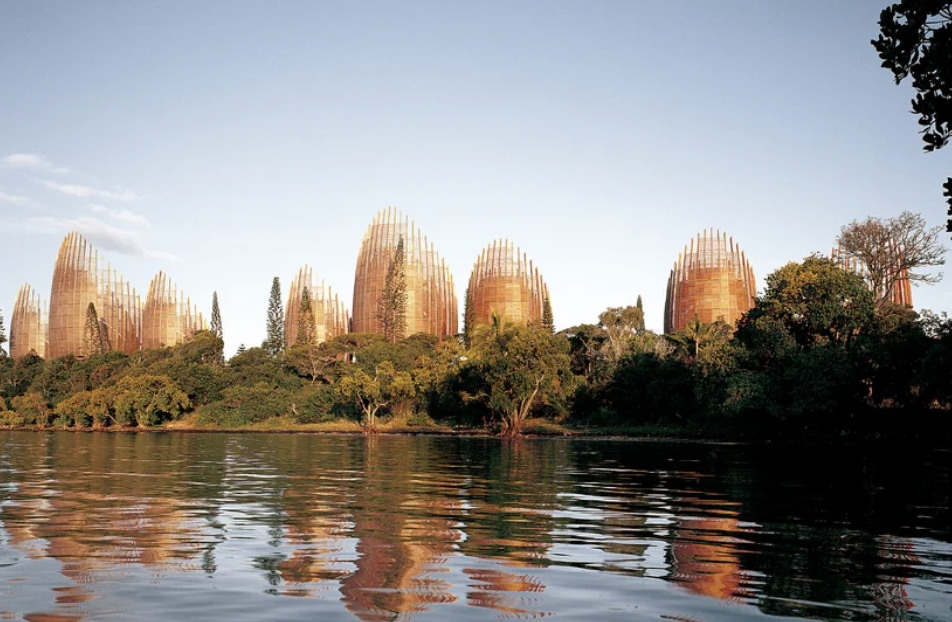

Renzo Piano rose to international fame with his collaboration it the 1970s with Richard Rogers, designing the famous Centre Pompidou in Paris. Its Radical facade drew attention to his practice, eventually forming his practice, Renzo Piano Building Workshop in 1981. Now, they operate with offices in Genoa, Paris and New York. With a career spanning over 5 decades and counting, his work spans from The Shard, Whitney Studio Building, Tjibaou Cultural Centre to modern day infrastructure.

Core philosophical commitments

1. Architecture as systems

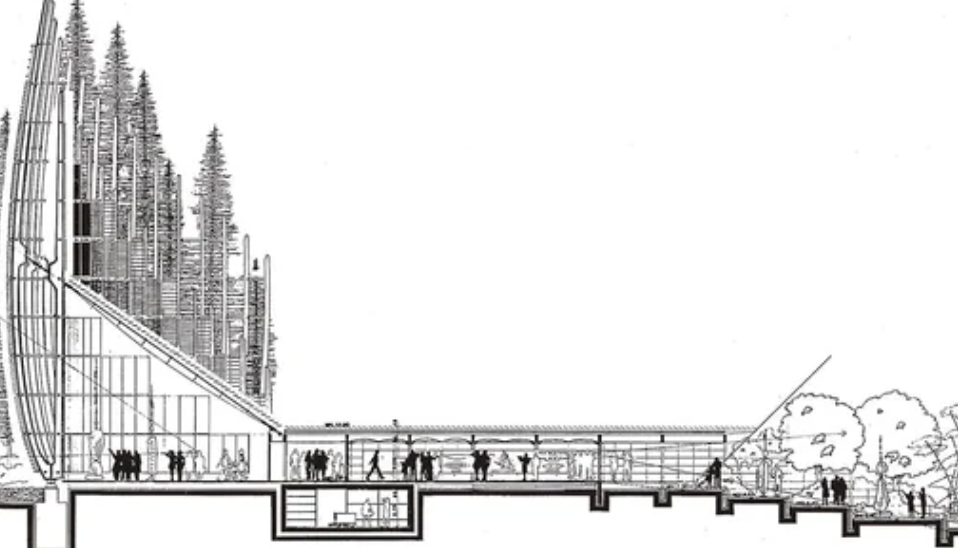

Piano sees architecture as a series of systems, including: lighting, ventilation, acoustics, thermal comfort and circulation. Through these systems, he tries to align it with human scale and expression, with each design aimed as an expression… a light roof, modulating facade, articulation of a canopy, a solution to environmental and programmatic needs.

2. Lightness and transparency

Piano speaks and builds with lightness and transparency in mind, with each building embodying this in different ways. A design could be structurally light with slender frames, long spans, and light in terms of its lighting with transparent materials and filtered daylight. He seeks to reduce the impact visually so paces feel more open and continuous within their contexts.

How the work is made — methods, tools and collaborators

Research, precedent and program analysis

When examining his studio, many observe that his projects begin with obsessive study of site context and environmental data. The team maps sun angles, wind patterns, circulation patterns and cultural context before beginning with the design.

Models and mock-ups

Although physical models play a key part, it seems that Piano’s studio relies on it more than others. While architects continue to experiment with digital modelling, Piano and his team rely on physical modeling, even building full scaled prototypes for complicated facades, roof details and surfaces just to analyze and critique it before construction. In this way, they are more traditional than other studios.

Environmental tuning

Piano was an early adopter of passive and hybrid strategies: brise-soleil, operable louvres, double façades, and natural ventilation in temperate climates. He couples these with mechanical systems when required, but the first line of defense is always the building form and skin. The Shard, for example, uses sophisticated façade engineering for insulation and solar control while offering visual transparency at the top floors.

Signature moves — recurring devices in his work

Structural elements exposed: exposed trusses, cable nets and slender columns appear throughout Piano’s work, as an artist and engineer collaborated on the design.

Façade modulation: rather than one flat skin, Piano uses iterative façade modules: sun-shading, brise-soleil, double skins, each with a site specific reason in mind.

Light wells and atria: many projects use dramatic atria and light wells to bring daylight into deep plans while creating social cores.

Case examples (brief)

Centre Pompidou (with Rogers) — radical early manifesto: services exposed, structure celebrated; learning ground for open, service-oriented architecture.

The Shard (London) — a mega-scale exercise in slenderness and high-performance skin: a tower that reads as a shard of light; sophisticated façade and floor-plate planning create varied workplace and public experiences.

Kimbell Art Museum expansion (Fort Worth) — a lesson in restraint and sensitivity: addition respects Louis Kahn’s original while delivering modern climate and curatorial standards.

Menil Collection expansion, New York / Piano’s museums — understated clarity: daylighting handled with extreme care, neutral galleries, human scale circulation.

Despite his fame, his work isn’t perfect and is still met with criticism, such as the environmental costs of his glass facades and bold design choices. Yet his response? More locally sourced material and a greater usage of the environment to their design. Piano’s enduring legacy is thus twofold: he demonstrated that sophisticated engineering and humane space-making are not opposites, and he modeled a practice that is simultaneously international and rooted in a workshop-based culture of craft-driven iteration, offering a practical blueprint for an era demanding both climate intelligence and civic generosity through an architecture that performs technically, delights the senses, and yields buildings that feel both contemporary and lasting.