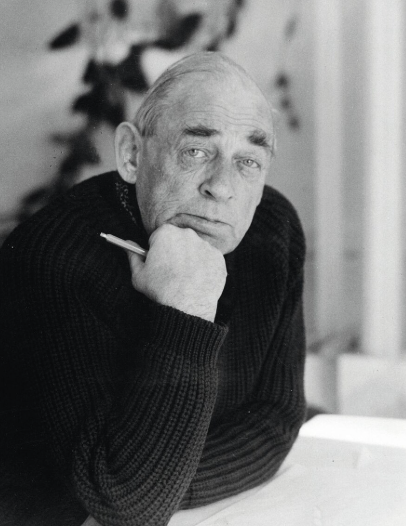

Alvar Aalto: The Human Modernist — Between Nature, Culture, and the Everyday

In the fast paced world of architecture, Alvar Aalto seems to get neglected in comparison to other architects of his time. He reintroduced the human body and natural landscape back into modern architecture, with his work often being called the ‘humanist of modernism’. He bridged the modern brutalist architecture with vernacular craft and nordic architecture. His work, including furniture pieces, can best be seen as instruments of comfort, light and care. This post explores Aalto’s life, design philosophy, and unique practice, examining how his synthesis of modernity and empathy continues to shape architecture today.

A Life Rooted in the North

Born in 1898 in Kuortane, Finland, Aalto spent his childhood in the midst of nordic nature, surrounded by lakes, forests and lights that would deeply shape his work. He studied architecture at the Helsinki University of Technology, graduating in 1921, a time when European modernism was rapidly spreading through the writings of Le Corbusier and the Bauhaus.

In his work, Aalto can be seen taking parts of brutalist or modernist architecture, its efficient plans, flat roofs, but refusing aspects of that ‘dehumanized’ place. He believed strongly in material choice, climate and psychology, a belief that guided him throughout his career, from his early modernist experiments to his later organic masterpieces.

Design Philosophy: The Organic Modernist

1. Humanism over Abstraction

Aalto rejected the cold rationalism of many modernist contemporaries. “Architecture,” he said, “should be a synthesis of life in materialized form.”

Rather than creating fixed grids of space like Le Corbusier did, Aalto wanted his projects to flow with human movement and psychology. In projects like the Paimio Sanatorium (1933), every element, including the angle of bed placement and colour of the wall, was designed to support those healing, showing his meticulous detail in design, and persistence in his belief.

2. Nature as Model and Material

Le Corbusier once linked architecture to machines, but Aalto compared them to trees. The forest became his design philosophy, yet also a main source of materiality, with birch pine and stone appearing commonly in his buildings. His spaces often mimic the patterns of nature — curving walls, branching circulation paths, layered light.

“We should work for simple, good, undecorated things, but things which are in harmony with the human being and organically suited to the little man in the street.”

3. The Gesamtkunstwerk

Aalto believed that architecture must satisfy every sensory experience, even the most minute details. Looking around his buildings, the furniture, lighting and even doors can be seen as one system. His famous furniture pieces, Savoy Vase (1936) and Bentwood Paimio Chair are the same, ergonomic comfort, materiality and organic form.

4. Light as Architecture

In Finland, where daylight is scarce throughout the year, light in architecture becomes a very valuable material. Aalto is one of the few who mastered the usage of natural light, learning how to place exact skylights, clerestories and soft surfaces to create warmth within interiors. His churches and libraries — particularly the Viipuri Library (1935) and Church of the Three Crosses (1958) — reveal a near-spiritual understanding of light as both physical and emotional substance.

Case Study: The Paimio Sanatorium (1933)

Aalto’s early masterpiece, the Paimio Sanatorium, embodies his humanist approach in every detail.

Form and Function: The building’s wings stretch into the forest like branches, maximizing sunlight and air circulation

Color and Detail: Soft greens, yellows, and blues were chosen for their psychological calm. Custom-designed furniture reduced noise and glare

Integration with Nature: Large windows frame forest views, and terraces blur the line between hospital and landscape. Nature becomes a form of healing.

Aalto once described Paimio not as a hospital, but as “a medical instrument.” It remains one of the most profound examples of his work and belief.

Legacy and Influence

Aalto’s impact extends far beyond Finland. He helped shape Scandinavian modernism into a softer, more inclusive movement that balanced functionality with emotional resonance. His influence can be traced through architects like Jørn Utzon, Glenn Murcutt, Peter Zumthor, and even Kengo Kuma — all of whom share his reverence for material honesty and sensory experience.

Today, as architecture grapples with sustainability, mental health, and human scale, Aalto’s principles feel prophetic. His belief that design should “stand in natural relation to man and to nature” anticipates today’s ecological and biophilic design movements.

A Philosophy for the Future

At its heart, Aalto’s work argues for architecture as a living organism — one that grows from context, breathes with light, and adapts to human life. He saw beauty not as luxury, but as necessity — something that dignifies ordinary experience.

In a time when architecture often oscillates between spectacle and efficiency, Aalto’s buildings remain a reminder that true innovation lies in empathy. His modernism was not about breaking with the past, but about continuing nature’s logic into the built world.

“Architecture belongs to culture, not to civilization.”

— Alvar Aalto

Conclusion: The Soul of Modernism

To walk through an Aalto building — whether the Villa Mairea, Finlandia Hall, or a humble library — is to experience modernism reborn as something tender and humane. Wood creaks underfoot, daylight ripples across curved ceilings, and the scent of birch softens the air. It is a kind of modernism that listens.

Alvar Aalto taught the world that architecture need not dominate or dazzle — it can care.

And in that quiet revolution, he gave modernism its soul.