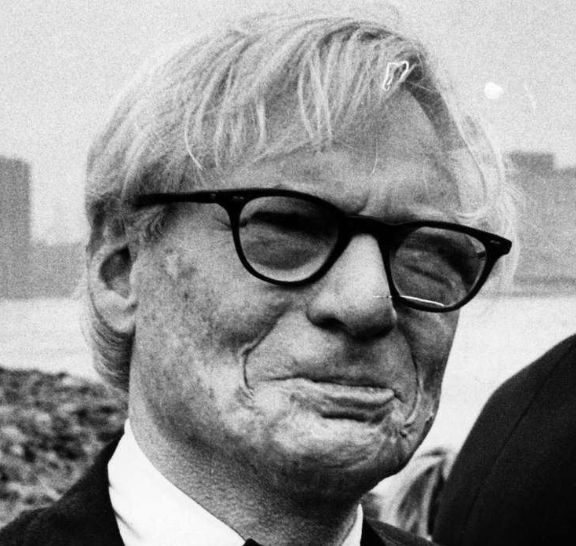

Louis Kahn: The Architect of Silence, Light, and the Eternal

Few architects have carried the moral weight of architecture as Louis Kahn. His buildings are more than buildings, but carries this timeless, silent feeling. To walk through a Kahn building is to enter a place where connection between human, material and nature exists, and questions the essence of architecture. Kahn’s work stands at the intersection of modernism and monumentality, of rational structure and metaphysical inquiry. He taught us that architecture is not only about what is built, but why it is built, laying down the foundation for generations of architects to come.

Origins: The Search for Meaning in Form

Born in 1901 in Estonia, Kahn grew up in Philadelphia, and became one of the prominent figures of mid-century architecture. He later studied at UPenn under Paul Phillipe Cret, being influenced by Cret’s use of Beaux-Art, and emphasis on precision, order and proportion in design, aspects that would distinguish his work later on from his contemporaries.

However, Kahn’s designs were never historical. After years of designing large scaled projects, he finally had his own distinctive view of architecture in the late years of his career, rationalism with spirituality. His works from the Salk Institute to the National Assembly Building of Bangladesh evoke deep spiritual meaning and use rational logic of modern construction.

Philosophy: The Nature of Being and Making

1. “What does the building want to be?”

“Even a brick wants to be something. It aspires to be an arch.”

Perhaps this is Kahn’s most integral question in his design process. His belief that every aspect of design, even the site itself has a spiritual nature to it, and that it was his job as an architect to enunciate it rather than hide or impose on it. It almost seems Kahn’s belief was rooted in vernacular Japanese traditions with spirituality in materials, like Shintoism.

For Kahn, this belief drove every aspect of his design. Concrete and bricks were used to give ‘spiritual order’, while soft materials were used to create a ‘light’ feeling. Structure, for Kahn, was not technical but moral, a visible expression of how materials hold and serve.

2. Light as the Maker of Space

He once said, “The sun never knew how great it was until it struck the side of a building.”

Kahn was obsessed with light, he believed it helped shape the building's structure and mood it created. In his Kimbell Art Museum (1972), Kahn used vaulted feelings and aluminium reflectors to diffuse natural light, creating a tranquil feeling. At the Salk Institute (1965), the concrete was selected to create different ‘glows’ as light changed throughout the day, turning it into a reflection of time.

Light, for Kahn, was not decorative. It was a spiritual structure, the source of architecture’s emotional power. It reveals form, animates material, and evokes transcendence.

3. The Servant and the Served

One of Kahn’s most original ideas was the line between ‘served’ and ‘servant’ spaces. In his buildings, corridors, ducts, and service zones are shown deliberately, as Kahn believed they are vital components of structure and function. The hierarchy in his design became a principle studied in architecture school, giving legibility in his plans. Architecture, for Kahn, was not just about enclosure, but about the relationships that sustain life within it.

4. Monumentality and the Eternal

Kahn was obsessed with timelessness in his designs. He studied classical architecture, taking key aspects like weight of stones, openings and negative space between forms to replicate a timeless spirit. He even went on to define this idea as “a spiritual quality, inherent in a structure which conveys the feeling of its eternity.” This can be best seen in his National Assembly Building, where he used simple but massive geometric forms, making the composition feel overwhelming, yet timeless and sacred.

Case Study: The Salk Institute for Biological Studies (1965)

Commissioned by scientist Jonas Salk, Kahn aimed to make the building a monastery for the sciences, yet also a place where people could gather with nature. Yet, it became one of his most ingenious designs, perhaps capturing the essence of his design philosophy better than any other ones.

Form and Space

Kahn created two parallel laboratory blocks with a central plaza in between, orientating the structure so it faces the pacific ocean. Between the two blocks, there is a stream of water, merging architecture directly with nature in a time where brutalist doctrine separated both.

Material and Light

Kahn’s use of concrete and teak wood balances permanence and warmth. The concrete is left raw and textured, revealing the imprint of its wooden formwork. Light floods the interiors from clerestories and skylights, animating the workspaces through the day.

Meaning

“The building is what it wants to be — a place worthy of the spirit of man,” Kahn said of the project.

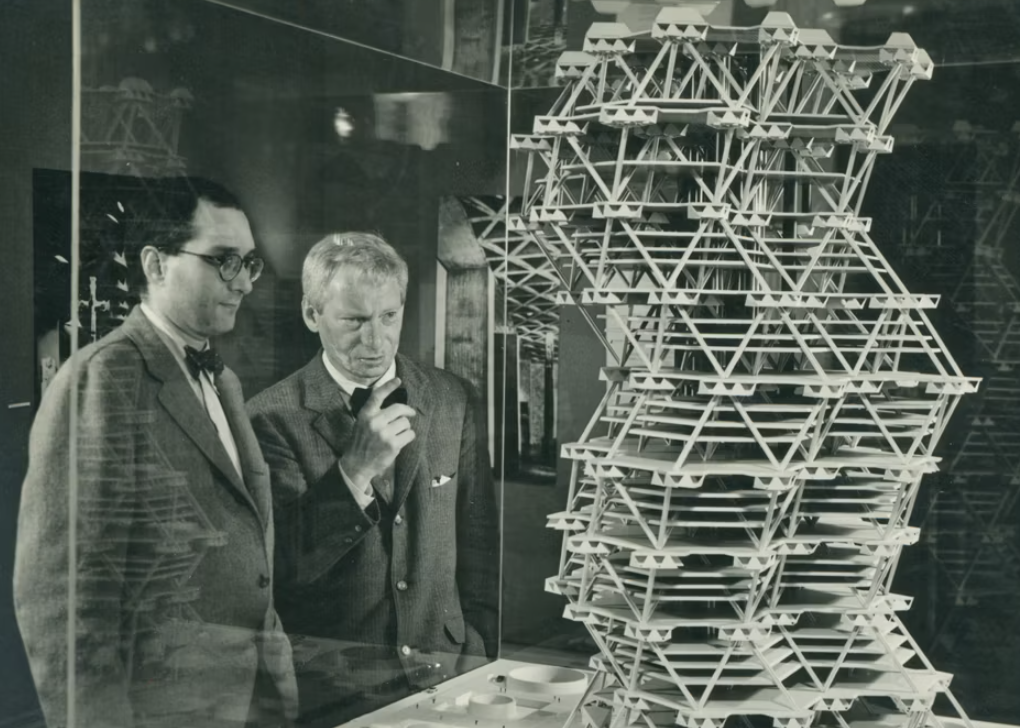

Method: Craft, Collaboration, and Intuition

Khan’s process was perhaps more traditional in method of working, perhaps due to the lack of digital tools when he first started his practice. He often starts sketches with charcoal, similar to Gehry, aimed to have ‘feeling’ in his drawings, and evoke the essence of form. He was also a large collaborator with other practices, including working with engineers August Komendant and Artist Anne Tyng to make his innovative designs come to life. However, Kahn was also meticulous in construction, often spending the most time on site to ensure everything was made to his standards.

Louis Kahn’s enduring legacy, which transcends stylistic schools to inspire architects like Tadao Ando and Peter Zumthor, gave modernism a soul by infusing form with meaning, stillness, and the movement of light. His buildings remain sanctuaries of stillness and dignity not because they followed trends, but because they speak to universal human emotions, transforming architecture into a timeless act of reverence—a meditation in concrete, brick, and void where light, the giver of all presence, reveals and conceals, celebrating the very existence of a place built not just for shelter, but for the spirit.