Kengo Kuma: Architecture of Disappearance — Nature, Craft, and the Poetics of Lightness

In an age filled with glass facades, Kengo Kuma’s work stands out instantly. Looking at his work, the usage of wood, vernacular methods and unique facades instantly jumps at you, making the building feel more lively than static. Kuma seeks to dissolve the boundary between building and environment by grounding his practice in vernacular Japanese craft, yet remaining technologically driven, becoming one of the most influential architects in the 21st century.

This blog post explores the evolution of Kengo Kuma’s practice, his design philosophy of “anti-object”, the methods and tools that underpin his work, and how his architecture offers an alternative to modern architecture.

From Tokyo to the World: The Roots of a Philosophy

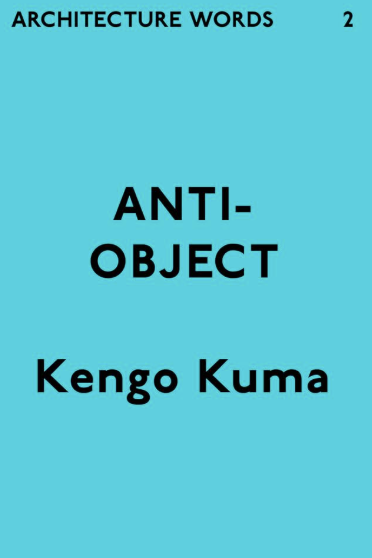

Born in Yokohama in 1954, Kuma experienced Japan’s rapid postwar modernization, where concrete skyscrapers took over the skyline. He studied under Hiroshi Hara at the University of Tokyo, and then travelled to New York to continue his studies. When Japan’s economic bubble finally burst in the 1990s, Kuma found himself questioning the time he lived in, and Japanese architecture. Rather than continue the imposing glass facades that quickly took over, his response was the opposite, a call for ‘weak architecture’, buildings that blurred the line with nature. In his 2008 book Anti-Object: The Dissolution and Disintegration of Architecture, Kuma articulated his core belief that architecture should not dominate but rather seek to integrate and collaborate with nature. A way of designing for ecological and psychological well-being in an urbanized world.

Design Philosophy: The Art of Disappearing

Kuma’s work is anchored in a few key ideas that form a coherent philosophical system.

1. Anti-Object — The Architecture That Vanishes

For Kuma, he defined the object as the architectural obsession of turning buildings into sculptural and isolated forms. By coining the term Anti-object, he seeks to reject this norm, emphasizing transparency and layering in material and design instead. This can clearly be seen in his work, where lattices are used instead of walls, roofs match the surrounding hillside, thin paper sheets instead of windows, almost as if it was an extension of the site's context.

2. Material as Mediator

Kuma believes in traditional Japanese craft, that material carries significant cultural value. Thus, when working on projects, Kuma tries to source local materials from the site, and integrates technology to create innovative facades that are distinct with his ‘design DNA”. He also collaborates with artisans and experiments with old materials.

For example, in the GC Prostho Museum Research Center (2010), Kuma adapted wooden joints from Kumiko joinery as a supporting lattice structure, while at the same time making it look ornamental through digital techniques.

3. Fragmentation and Light

Kuma’s architecture avoids using heavy materials or volumes, but he seems to use this fragmented layer technique to let people, light and air flow freely. In this way, light and air become materials that are filtered and used through the facade, creating a connection between interior and exterior. In projects like the SunnyHills Store in Tokyo and the Asakusa Culture Tourist Center, sunlight is choreographed to shift mood and time, transforming everyday life into a sensory experience.

4. Contextual Empathy

“I want to create architecture that fits into its surroundings as naturally as a forest fits into the earth.”

This empathy extends to urban settings as well. The V&A Dundee (2018), for instance, echoes the cliffs of Scotland’s northeastern coast — a cultural building that feels geological, carved by wind and water rather than imposed upon the site.

How He Works: Process and Tools

Kuma’s process merges handcraft and technology in every project, and his office, Kengo Kuma and Associates, operates with designated teams of modelmakers, material researches and fabrication teams across tokyo paris and beijing. Here are some of the most important aspects of his process:

Material Research

Each project begins with material experimentation and research. His studio houses one of the largest material libraries, and materials are often extracted and tested for texture, transparency and porosity. Kuma often prototypes 1:1 scale panels to study light and shadow behavior, sometimes collaborating with engineers and local craftsmen.

Digital Fabrication Meets Tradition

While having the traditional side to practice, Kuma usually uses parametric modeling, CNC milling, and robotic assembly to create his facades, pushing the limit of material he chooses.His Yusuhara Wooden Bridge Museum (2010), for instance, uses advanced joinery simulations to reimagine ancient temple carpentry with structural precision.

Case Study: The Japan National Stadium (Tokyo, 2020)

The Japan National Stadium, completed for the 2020 Tokyo Olympics, is perhaps Kuma’s most large-scale project, yet also a work that encapsulates his philosophy.

Material palette: over 47,000 pieces of Japanese cedar and larch sourced from all 47 prefectures, celebrating regional identity.

Environmental strategy: deep eaves, layered canopies, and natural ventilation to reduce energy load.

Cultural symbolism: the stadium’s tiered wooden horizontality echoes traditional hōryū-ji temple roofs, while the garden terraces blur the line between city and nature.

When asked about his work, Kuma described the design as a living forest within the city, attempting to reintroduce human touch to modern architecture. The project demonstrates how even large civic architecture can feel intimate and local when designed through material empathy.

Kengo Kuma’s architecture consistently gestures toward healing—for both the natural world and the human spirit—by treating buildings not as shelters from nature, but as membranes within it. This ecological intimacy carries a psychological dimension, where quietness, tactility, and light act as antidotes to modern overstimulation. His philosophy of “weak architecture” advocates not for fragility, but for resilience through humility, promoting flexible, adaptable, and less wasteful designs as a critique of the egocentric “starchitect” era. While some critics note that his refined approach risks becoming a repetitive global aesthetic of lattices and screens, even detractors acknowledge the sincerity of his impact in re-centering materiality, craft, and context.

In contrast to the glossy globalism of the early 2000s, Kuma’s work invites a slower, more aware engagement with our surroundings—to touch, look, and breathe. His architecture suggests a future built on softer, more sensitive ones that dissolve boundaries between building and ground, people and nature, the old and the new.